Picking a perfectly ripe thimbleberry takes focus.

Squeeze it, and it turns to jam. Pinch it quick with two fingers instead of nimbly with three, and you’re likely to send the delicate red berry cap flying, and watch sadly as it slowly sails to the ground.

“You have to be totally in the moment,” says Berry Wijdeven, who knows a thing or two about berries.

Wijdeven will easily spend over an hour picking thimbleberries near his house in Tlell in summertime.

It’s something Wijdeven enjoys, which is a very lucky thing for fans of the Haida Gwaii chocolate maker’s locally-flavoured gelatos and chocolate bars.

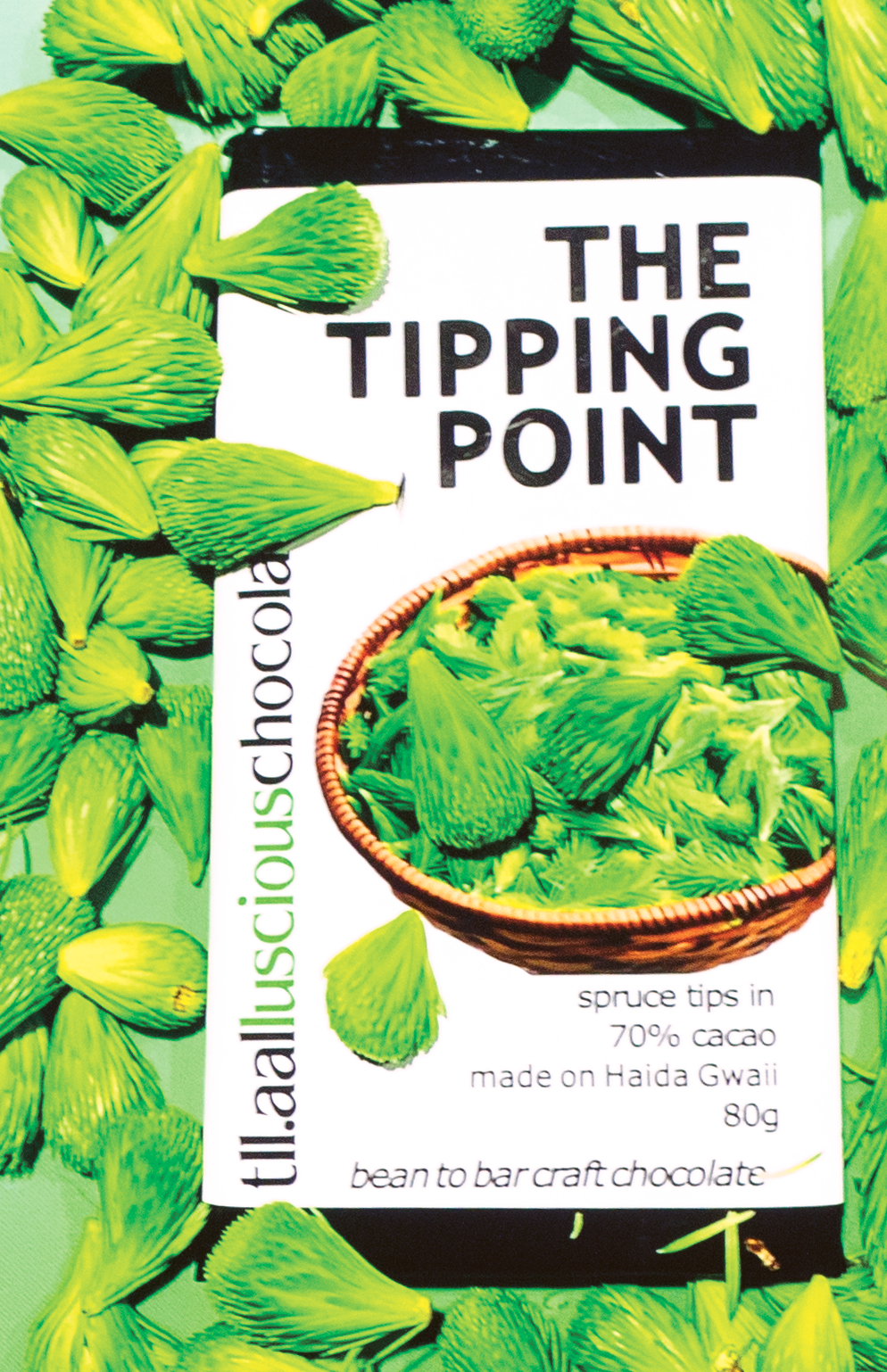

Thimbleberry chocolate is one of Wijdeven’s favourite flavours so far, along with spruce tip, salal berry, and a creamy, caramel-y white chocolate made with golden chanterelles.

For people with more daring tastes, Wijdeven makes This Won’t Hurt a Bit — a stinging-nettle chocolate — and Eat Your Greens — a microgreens chocolate some liken to matcha green tea.

Berry Wijdeven was invited to talk about how he makes and flavours his own “bean to bar” chocolate on Oct. 26 as the keynote speaker for this year’s Sandspit Wild Harvest Festival.

It was actually microgreens that got the idea growing.

After working for 30 years as a government biologist and marine planner (and not-working as a talented cartoonist), Wijdeven was thinking about a fun job for retirement when Covid hit and fresh veggies got even tougher to find on island.

So, Wijdeven set up a grow room for the first product of Tll.al Luscious Foods: microgreens. He harvests the fresh-tasting greens every 10 days, and deliveries some each week to local restaurants and grocery stores.

YouTube was a helpful teacher over the four or five months it took to figure out the details of growing store-ready microgreens on schedule.

Soon enough, with all the food channels he was following, YouTube began pushing him toward chocolate-making videos.

Wijdeven said he tried to fight it and stick to fresh vegetables, but the nights are long in Tlell and as a Dutch guy, chocolate flows in his DNA.

What got him hooked were videos by John Nanci, aka the Chocolate Alchemist, who came up with a way to make bean-to-bar chocolate at home with DIY gear that doesn’t cost a zillion dollars.

“Bean to bar” is craft chocolate, made starting with dried cocoa beans from a particular country or even a particular farm, rather than buying ready-made chocolate in bulk and blending in custom flavours.

It’s way more work, says Wijdeven, but also way more satisfying.

For one thing, the flavour profile of a cocoa bean differs much like a wine grape or a coffee bean — it depends on the local climate and weather.

For another, by buying from a direct-trade seller, Wijdeven knows the cocoa farmers are decently paid.

Cocoa grows in large pods in humid, rainy tropical forests.

“If it’s done right, you can grow them in the forest without having to cut all the other trees down — they like a bit of shade,” Wijdeven said.

“So, in an ideal world, it’s ecologically quite sustainable.”

Like coffee, cocoa beans are actually fruit seeds, not beans. Farmers use the white pulpy fruit that surrounds the seeds to ferment the “beans” before drying so they take on a richer, more chocolate-y flavour.

A couple years ago, when Wijdeven had finally made or gathered all the gear he needed to roast, crack, de-husk, grind, temper and flavour cocoa beans into chocolate, the first thing he discovered was that a 160-pound bag of cocoa beans is too heavy to lift off the Masset barge at 2 a.m.

But after getting creative with his pickup truck, Wijdeven got creative at home.

At first, he blew the husks off his roasted beans with a hair dryer and a mixing bowl. Today he uses a DIY “winnowing” machine powered by a shop vac.

A key step is the “mélange,” when the roasted, de-husked cocoa nibs get ground and blended into liquid chocolate by a pair of granite rollers.

“I’m told my chocolate is very creamy, and I think it’s because I let it mélange for 72 hours, and most people do it for 36 to 48,” Wijdeven said.

Next comes the step that gave Wijdeven the most trouble: tempering.

Unless it’s crystallized using some pre-tempered chocolate or prepared cocoa butter, Wijdeven said newly made chocolate will get very bad tempered indeed.

With no tempering, chocolate will separate in a day or two into something like oil and chalk. Add the least bit of water at this stage, and the chocolate will seize up so it’s too hard to eat, which is why all the flavouring ingredients have to be dried or oil extracts.

But, when melted, tempered, and then cooled in molds to just the right temperature, the chocolate crystals stay locked together and a molded bar gives a satisfying snap when you bite or break it.

Wijdeven said dozens of Haida Gwaiians have offered to help him as taste-testers. He all set in that department, but is always looking for new flavour ideas.

Like the Zotter chocolate factory in Austria, which has an actual graveyard with headstones for all the flavours that didn’t quite work, Wijdeven has had some notable failures.

Deer meat didn’t take, rose hips were too weak, sea asparagus was all salt, and liquorice fern, while delicious, made too much a mess of the trees.

Thankfully, Wijdeven is a man of many ideas, and lives on an island where lots of other people have ideas, too.

When someone in Sandspit asked if he had made huckleberry chocolate yet, Wijdeven said no, not yet, because he doesn’t think it has a lot of flavour.

“But I was told by a local that I was wrong, so I’ll try that,” he said.