Over a decade ago, First Nations led a diverse, province-wide movement to stop the Enbridge Northern Gateway Pipeline and keep crude oil supertankers out of our northern waters — and won. In 2019, shortly before you elected me as your Member of Parliament, Canada made it official by passing the Oil Tanker Moratorium Act.

With a federal election looming, that law, and the decade of work it represents, now hangs in the balance.

No sooner than the ink had dried on the moratorium, Conservatives got to work. First up was a private member’s bill by an Edmonton-area Conservative MP that aimed to repeal the law entirely. It was voted down. Then, in his campaign to become Conservative Party leader, Pierre Poilievre frequently pledged to scrap the tanker moratorium. After winning, it became his constant refrain.

Now, Poilievre is promising to “super charge” the oil sector, ramping up production and building an “energy corridor” (read: oil) to our coast. Conservatives cannot wait to get rid of the law – our law – that stands in the way of their big oil ambitions.

The history of protecting our coast from oil goes back to the 1970s and a plan to build an oil port in Kitimat – at that time to import oil to Canada. Frank Howard, the first NDP Member of Parliament in our region, stood in the House and stated bringing oil tankers to our inside waters was, “inimical to Canadian interests, especially those of an environmental nature.” After a public inquiry and significant community opposition, the oil port was shelved and a voluntary tanker exclusion zone established.

When Enbridge came along with its Northern Gateway plan, memories of the first fight against tankers still lingered. This time, First Nations led the resistance, which extended up and down the coast and all the way up our rivers, where nations feared the impact of a bitumen spill on wild salmon. Coastal First Nations invoked traditional laws and passed their own tanker ban.

I remember massive rallies in Prince Rupert with Haida and other hereditary chiefs in regalia leading over a thousand people in a march down Third Avenue. Citizens packed into hotel ballrooms and community halls to testify in front of the Harper Government’s Joint Review Panel.

The then-Village of Queen Charlotte (now Daajing Giids) and the Village of Masset passed official resolutions and over a dozen municipalities, including Prince Rupert, Terrace and Smithers, followed suit.

In Kitamaat Village, the Haisla hosted an all-nations summit to galvanize opposition. In Hartley Bay, Gitga’at matriarchs knitted a four-kilometre-long chain out of yarn and strung it across Douglas Channel. My predecessor Nathan Cullen carried the region’s message to Parliament, while on the front steps of the House of Commons, Guujaaw and the late Beau Dick cut up a copper in a powerfully symbolic act of defiance.

Looking back, it was a time of remarkable unity. The Harper Conservative government, of which Pierre Poilievre was a member, responded by calling the good people of the Northwest “enemies of the state.”

Today, the politics look a bit different but the stakes are the same. Bringing crude oil to our coast means risking a spill that simply can’t be cleaned up. It means risking a marine ecosystem that’s the foundation of our coastal economy and a source of food for so many. And it means entrenching a fossil fuel energy system that’s burning the planet.

In our riding, my Conservative opponent Ellis Ross doesn’t support the Oil Tanker Moratorium Act. He told a Senate Committee he thinks it treats the oil industry “unfairly.” His boss, Pierre Poilievre, remains determined to rip up the moratorium at the earliest opportunity.

It’s time to vote, folks. Let’s vote like our coast depends on it.

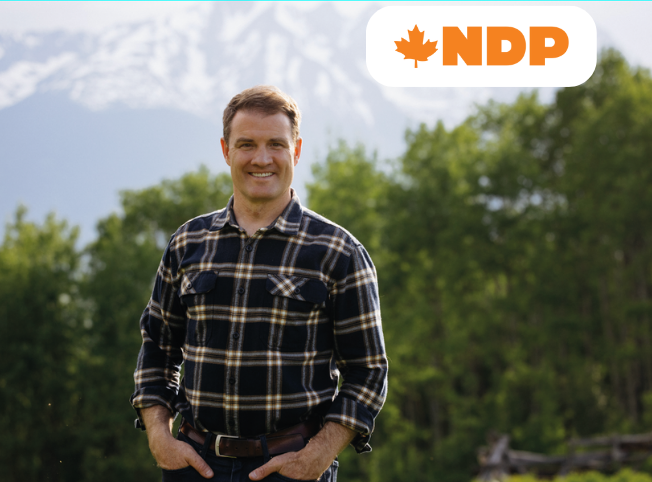

Taylor Bachrach is the incumbent Member of Parliament for Skeena-Bulkley Valley and is running for re-election in the April 28 federal election.